Ha'aretz.

It takes courage to openly state what the International Monetary Fund's researchers are saying. Such a statement would have been inconceivable five years ago.

Nitzan Horowitz

Only a few minutes’ stroll along Pennsylvania Avenue separates the massive complex of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund from the much smaller White House. Perhaps the size difference symbolizes the relative degree of importance and the center of gravity: the economic headquarters are the real fulcrum of power; the White House is for tourists.

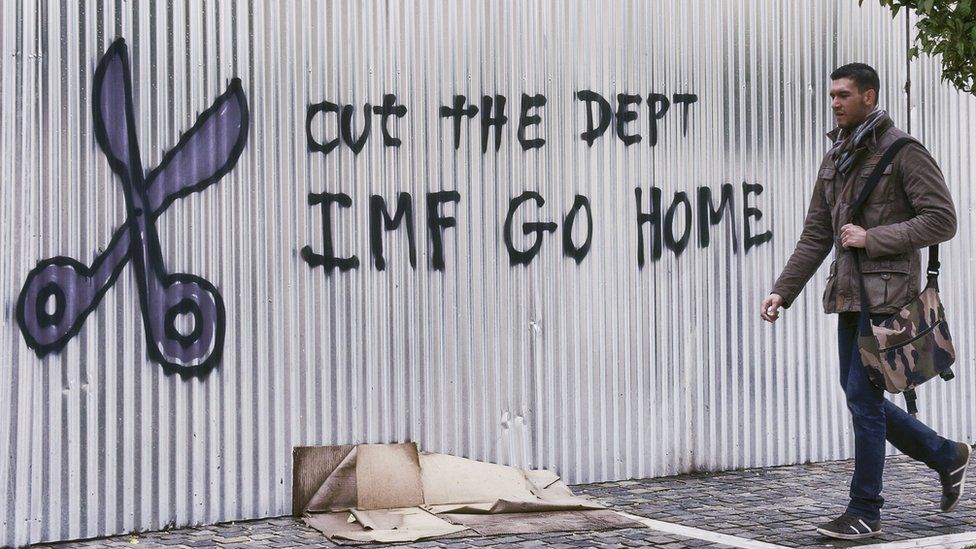

Ever since these two economic institutions were founded at the end of World War II, they’ve affected people’s lives far more than any U.S. president or the prime minister of any country. The IMF and World Bank are not only powerful executive instruments; they’re also ideological bodies. For more than 70 years, they’ve served as the most effective disseminator of a clear political ideology: the rule of capital. This is why what’s just happened can be likened to an earthquake.

Senior economists at the IMF, not usually people suspected of having a shred of sympathy for social ideals, have dropped a bombshell. “Neoliberalism: Oversold?” – a report published in the IMF’s flagship magazine – determines that the neoliberal approach, which has shaped the world for the last two generations, has failed.

This challenges concepts that were regarded as unassailable, such as the need to reduce the public sector; the need for fiscal restraint; the reduction in regulation; a complete opening of markets to foreign capital; and across-the-board competition. But it turns out these measures haven’t delivered the goods. They suppress growth and entrench inequality, leading to financial crises, according to the report’s authors.

How is this possible? After all, this is what is taught in our universities, what most of the media recites, and what Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu so loves to explain. Many of these mantras have been drummed into people’s heads thanks to massive funding by research foundations and institutions, as well as a more brutal imposition of neoliberalism on countries by using a carrot-and-stick approach in the shape of loans and sanctions.

Neoliberalism is in the IMF’s DNA. That’s why this report is so revolutionary. It reflects the sharp debates taking place in financial institutions and academia since the global crisis of 2008.

Even the term “neoliberalism” is now perceived as some kind of provocation. Those usually using it are the IMF’s opponents. It takes courage to openly state what the IMF’s researchers are saying: “Some aspects of the neoliberal agenda probably need a rethink,” said lead author Jonathan Ostry. “The [2008] crisis said, ‘The way we’ve been thinking can’t be right.’” Such a statement would have been inconceivable five years ago.

The research focuses on two main corollaries of neoliberalism: the removal of barriers that impede the free flow of capital; and budgetary constraints on services. The researchers conducted a comprehensive study between countries and found no proof that opening markets to unregulated capital flow increases growth. A tsunami of foreign capital can actually lead to instability and financial crises. I had to pinch myself in order to believe I wasn’t imagining the following sentence – a recommendation to consider imposing restraints on the flow of capital. Even in relation to the “fat and thin” mantra (the public and private sectors), the researchers courageously questioned the sanctified principle of giving total priority to debt reduction over services provided by governments to the public.

The bottom line focuses on an issue that was neglected but now turns out to be fundamental: inequality. The neoliberal agenda is supposed to encourage growth. However, its principles deepen societal gaps, thereby causing instability and impeding growth, the authors say. In order to contend with this problem, IMF researchers even use the concept of “redistribution.” Again, I had to pinch myself.

These conclusions require us to take stock – certainly in Israel, which has one of the highest levels of inequality and which, over the past decade, has slid to the bottom of the list of developed countries in terms of economic disparity. But what are the odds of this happening?